For this statement to be remotely true, it must be rendered as “No individual acting in a non-official capacity is above the law.” However, even in this iteration, it is pre-supposed that “the law” in question is just, moral, and right. For example, an obstetrician may be asked to perform an abortion, which is now a legal medical procedure. He can still refuse based on a higher moral authority, so in that case, he is acting as if he were above the particular law allowing abortion on demand.

Moreover, since abortion once was illegal, the Supreme Court decision that permitted it was written by a group that by definition had to have been above the law. A moment’s thought will convince you that having the power to change an existing law places one above the law.

Traditionally, the law-making or law-changing function of our government has been in the hands of the legislatures, but dating back to Marbury v. Madison (1803) this became muddled, perhaps fatally so. Chief Justice John Marshall was able to create the notion of judicial review out of whole cloth by writing a decision favorable to the sitting president (Jefferson), under the novel theory that the petitioner’s demands were “unconstitutional.”

Ironically, although Marbury would greatly expand the powers of the Court, in the actual (instant) case, it served to limit the powers, as the Court would not grant William Marbury the writ of mandamus that he wanted. In a further irony, the finding against petitioner Marbury would limit the expansion of the federal courts, at least temporarily.

In possibly the greatest irony of all, even though the decision gave Jefferson his desired short term outcome, he would later (1819) lament the case, noting that “The constitution, on this hypothesis, is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please.”

Let it be noted that in Marbury, Jefferson acted above the law by refusing to deliver William Marbury the commission certifying his appointment as a judge; and Marshall acted above the law by creating an entirely new justification to allow this.

Marshall argued that the Court did not have authority to grant Mr. Marbury his claim, while Marbury’s side argued—with great logic and indeed foresight—that the Constitution was only intended to set a floor for original jurisdiction that Congress could add to. Marshall contended that Congress does not have the power to modify the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction, but in so doing expanded that very jurisdiction by creating judicial review!

Thus was raised the big question of what happens when an Act of Congress conflicts with the Constitution. Marshall held that Acts of Congress that conflict with the Constitution are not law, and the Courts are bound instead to follow the Constitution. He noted that there would be no point of having a written Constitution if the courts could just ignore it. “To what purpose are powers limited, and to what purpose is that limitation committed to writing, if these limits may, at any time, be passed by those intended to be restrained?”

This is truly stunning. In that very case he had just expanded the powers of the unelected Supreme Court, putting it—by any standard—above the law, as well as above Congress. More importantly, where has the Court been all these many years in which literally thousands of laws have been passed that are well outside the Constitution?

If Marbury means anything, over the nearly 150-year-long bold expansion of federal authority, there are countless times that the Court should have intervened.

Now, let us venture beyond theory into the practical. Article II, section 3 of the Constitution enumerates one cardinal responsibility of the President: “[He] shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed…”

Clearly, the immigration laws are not being enforced, and while the Executive branch should be held liable, there are also many in the legislative arena who would agree with the non-enforcement. Although the cover story for the lack of enforcement is some sense of higher justice, the real reason is pure politics and nothing more. The Democrats believe that illegals (presumably after an amnesty) will generally vote for their party, and many Republicans—including Bush apparently—are owned by the slave labor, hospitality, banking, or education lobbies, all of which are vastly in favor of the illegals.

Meanwhile, every single poll shows overwhelming public support for aggressive enforcement. What better example of being “above the law” can I proffer than intransigent non-enforcement despite public demand?

The reverse of the immigration situation is drugs. As I have said before, if alcoholic beverages are legal, no possible argument can be made in favor of keeping certain drugs illegal. And, the benefits of legalizing them so outweigh the negatives, that it should be a no-brainer.

Street crime would be drastically reduced, and the prison population, bulging with minor drug offenders, would drop by more than 30 percent, according to some estimates. The only negative would be one we currently have, whereby drug-addled individuals ruin their lives. Certainly, there are many alternative ways to ruin one’s life, including alcohol abuse. Absent drug laws, though, what in the world would law enforcement and the courts be doing?

Only drug enforcement and tax collection emerge as areas where no one is above the law, and this is for the very same reason: It’s all about the dollars, and no one is above the dollars.

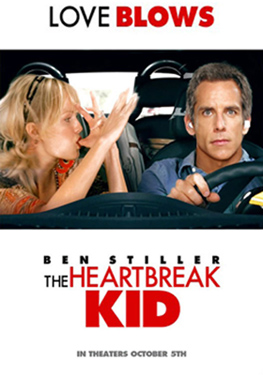

I had no intention of posting a review of this pic until I compared many so-called “professional” reviews with the reality of what I saw in the theater. Certainly, reasonable people can differ on a film, but not only did so many reviews get basic plot details wrong, a goodly number of the critics filtered the movie through a mélange of their own neuroses.

I had no intention of posting a review of this pic until I compared many so-called “professional” reviews with the reality of what I saw in the theater. Certainly, reasonable people can differ on a film, but not only did so many reviews get basic plot details wrong, a goodly number of the critics filtered the movie through a mélange of their own neuroses.