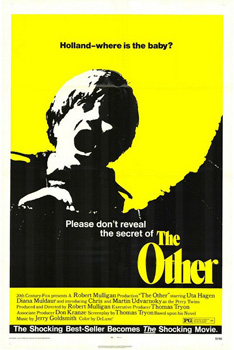

The best antidote to the current over-produced under-written fare is to go back into the archives, and rediscover (or discover for the first time) a gem. Let’s take a look at a splendid thought-provoking melodrama from the 1970s—The Other.

The setting is rural Connecticut in the summer of 1935. Helmer Robert Mulligan and cinematographer Robert Surtees create a creepy vibe from the very first shot. This is not idyllic, Norman Rockwell New England.

The opening long shot of the woods gradually zooms in on 11-year-old Niles Perry (Chris Udvarnoky) at play with his twin brother Holland (Martin Udvarnoky). Eagle-eyed viewers might notice from the outset that the two boys are never shown in the same frame, but the fun is just beginning.

Niles has a small tobacco tin stuffed in his shirt, and he looks inside to examine a young boy’s treasures, which include the Perry family ring, originally owned by his grandfather. The boys reconvene in the apple cellar—a place forbidden to them after their father was killed there some months earlier. However, their cousin Russell (Clarence Crow) has spotted them, and threatens to squeal to his father, their Uncle George (Lou Frizzell).

After Russell leaves, Holland goes into the barn and kills Russell’s pet rat. (“A rat for a rat,” he says.)

Gradually, we begin to put together the extended family arrangement. The Connecticut property has been in the Perry family for years, but presumably upon the death of the twins’ father, George’s family—which besides Russell includes his wife Aunt Vee (Norma Connolly)—moved in. The twins have an older and pregnant sister Torrie (Jenny Sullivan), married to Rider Gannon (John Ritter).

Rounding out the group are the twins’ depressed and alcoholic (after her husband’s death) mother Alexandra (Diana Muldaur), and the maternal grandmother Ada (Uta Hagen). There is also the housekeeper Winnie (Loretta Leversee) and farmhand/handyman Mr. Angelini (Victor French).

This entire group lives on the property, but, as we shall see, are not exactly one big happy family.

The bond between Niles and Ada is extraordinarily strong, one reason being that they both have psychic abilities. Niles will correctly predict the sex of the upcoming baby, but this is small potatoes compared to “The Game” played by Ada and Niles. The Game is essentially a highly developed exercise in imagination, or remote viewing. We first see it when Niles imagines that he is the crow flying overhead, and accurately describes it from the bird’s point of view. Niles uses it later to figure out how a magician performs a trick.

The twins don’t have to worry about Russell ratting them out, as he meets his demise jumping into a haystack in which a pitchfork is hidden, with its tines pointed up at just the right angle. If anyone is blamed at all, it is Angelini, but the family, except Aunt Vee, regards it as just a tragic accident.

However, more “accidents” are to come. Alexandra suspects that Niles might have the ring, and searches until she finds it, along with a severed finger, in the tobacco tin. Niles says he got the ring from Holland, a struggle ensues, and Alexandra falls down the back stairs, rendering her paralyzed, and unable to walk or talk.

Another strange death occurs after a neighbor, Mrs. Rowe (Portia Nelson), catches the boys in her barn trying to steal some preserves, and reports it to Uncle George. One of the twins, dressed up as a magician, and knowing that the old lady is deathly afraid of rats, scares her with one right into a fatal heart attack, while coming over to supposedly apologize to her.

After Mrs. Rowe’s body is discovered, Ada finds Niles in a nearby church, and confronts him with Holland’s harmonica, which was found at Mrs. Rowe’s house. It is there that she points to an image on the stained glass, which she calls “The angel of the brighter day.” Niles says that Holland went over to apologize and scared Mrs. Rowe, whereupon Ada drags Niles to the cemetery to show him that Holland died that March! The ring, which Ada says is cursed, was buried with Holland, or so she thinks.

Ada taught Niles the game to conjure up his brother, but now realizes that the game has gone way too far, and gets him to promise that he will not play it anymore. Alas, he can’t stop, as she observes him later that evening sitting on the floor talking to an empty chair, in which “Holland” is sitting. Flashbacks reveal that Holland killed his father for the ring. More than that, Niles, far from needing psychic coaching from Ada, projected himself into Holland’s corpse lying in the funeral home, and cut off his swollen finger along with the ring, supposedly at Holland’s bidding.

In the film’s final act, the baby is born, and some time later, Rider and Torrie go out for the evening. In the middle of the night, though, Niles awakes with a start, and runs to the baby’s room, to see that she is gone, eerily re-creating the Lindbergh kidnapping, in that a ladder is outside the window. A massive search ensues.

Niles runs off into his safe apple cellar and keeps repeating, “Holland, where is the baby?” Ada hears this, and now believes that she is responsible for multiple deaths, and that Niles cannot be rehabilitated. Little does she know that his psychic abilities far exceed hers, and he was long gone before she ever taught him “The Game.” Even though her words could save Angelini from mob justice, as the baby is found dead in one of his wine casks, she immediately attempts a murder/suicide. She dies, but Niles is able to escape, with the rest of his family being none the wiser.

Several interesting themes are in play here. It is clear that Holland was always the evil twin, but Niles (the younger by 20 minutes) went along with the schemes. We are left to guess whether or not Alexandra suspected what was going on when both twins were still alive.

A prominent theme is talent being squandered. Niles could use his powers for good, but other than predicting the sex of the baby, prefers to use them for ill intent. Likewise, for all her alleged psychic abilities, Ada is absolutely clueless about the worsening situation, and the danger to her family. Even after she finds out that Niles is psychotic, she has no problem leaving him with the baby.

But, she is not the only one in denial. Most of the rest are quite willing to blame the deaths of Russell and the baby on Angelini, and it is especially telling that they invoke the Lindbergh kidnapping (surely contemporary as key evidence was found in that case in September, 1935) as a model for their tragedy. Mrs. Rowe was a convenient heart attack victim, and Alexandra, always drunk, just fell down the stairs.

We wonder why Niles targeted the baby. In all other cases, revenge was exacted against those who would expose him. One possibility is that Angelini discovered the truth, and this would be a good way to get rid of the hired hand, albeit at a terrible price. Another is that the baby will draw Ada’s attention and love away from him.

Ada becomes the avenging version of the angel of the brighter day at the end, and in keeping with her hapless schemes, fails at that, as well. We are reminded of Polonius in Hamlet, all full of supposed wisdom, but in reality, little more than a windbag, and a harmful one at that.

Finally, Tom Tryon darkened the screenplay from his novel, in which Niles is institutionalized. This was the right cinematic decision, since it is so much creepier having the perp living among the victims, unsuspected. As the final shot of Niles in the window fades, we speculate on who will be next.